Even today there are critics describing Karol Wojtyła as a “political” Pope. But if it that was the case, if his reading of history and the world were overwhelmingly political and ideological, how could he intuitively understand, immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall, that the end of communism does not mean the victory of the “other”, capitalism? It did not, therefore, automatically mean the disappearance of unmeasured areas of poverty, much less huge differences in the distribution of goods.

John Paul II made this clear in Mexico in May 1990, during a meeting with a group of entrepreneurs. Many in the West were moved, if not scandalized, by this speech. And so, when Karol Wojtyła was portrayed as a vehement anti-communist, immediately afterwards he was accused of anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism. It was absolutely impossible to understand that he was looking at events from a different point of view. From a theological point of view. Yes, of course, the Pope was convinced that Christianity has the power to liberate peoples and nations. But it was about liberation, which, although undoubtedly with social and often political consequences, was driven primarily by spiritual, evangelical inspiration. This is why I keep saying that the pontificate of John Paul II must be considered and judged globally, in its entirety. This way one can finally “see” how in the first years the activity of the new Pope arriving from the East did not focus solely on the fight against atheist communism. From the outset, however, it has faced both the great challenges of a “bipolar” world then plunged into cold war, divided into two opposing zones of influence, as well as the dramatic challenges that underpin serious and unresolved problems of justice and peace.

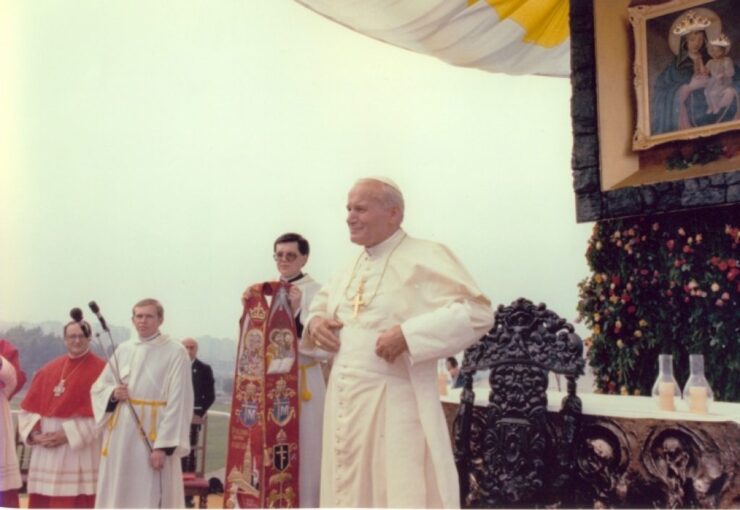

With the permission of Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz – “At the side of the Saint”

St. Stanislaw BM Publishing House, Krakow 2013